Multigenerational Language Barriers: The Desire for Closer Connection to Cantonese Culture

“I’ve lost the key to my culture.”

I spoke with my GuPo or Grand Aunt, on the phone every week. “Hello? Chlody? GuPo. You busy?”

No matter how busy I might have been with finals or work, I always tried to make room for these conversations that I held so preciously.

For her, I was just another person on her long list of family and friends to catch up with. For me, it was a deeper connection to my Toisanese roots through an elder.

“Sik Zo Faan Mei Aa? (have you eaten?)” It is most often what I’d hear at family dinners or on phone calls. Although never truly learning the language, I was still able to connect to our shared heritage through a love of food.

After moving to the East Coast for school, we fell into a routine of Facetiming for a few hours once a week to cook dinner for the past three years. I would work late and cook at 10 p.m. while she was on the West Coast just starting her dinner at seven.

Tens of thousands of Toisanese immigrants left China for America due to the economic downturn, starting in the 1850s and continuing through the 1930s primarily, leaving many hungry for food and opportunity. Because of this, we use Sik Faan La Ma as a term of endearment, greeting, or love.

During my interviewing process for this project, my GuPo passed away. We had talked about sitting down together reminiscing over tea, detailing her journey to the States, but we never got to do it on tape.

Patricia Jue, Ted Mon Gong, Anita Chu Gong, Young Chong How Chu, Tim Gee, Lorraine Pon Gee, Thomas Kai Gee (left to right)

Patricia Jue, Ted Mon Gong, Anita Chu Gong, Young Chong How Chu, Tim Gee, Lorraine Pon Gee, Thomas Kai Gee (left to right)

From what I remember, her story, while uniquely hers in character, resonates with the many stories people shared with me of their own families. Parents move to the States for better opportunities. With their children born in the States, the pressure of assimilation leads them to reject their parents’ language in favor of English-only assimilation.

To many Chinese Americans, the mark of a language barrier is what made them feel the societal pressure to be better “Americans.” Because that’s what we do, we feel like the only way to exist in this country is to assimilate completely, abandon our cultural identities and never look back.

Thousands of Cantonese and Toisanese second or third-generation Americans struggle with bridging the generational culture and relationship gap with their parents and grandparents. It’s a paradox. Our parents had to lose their identity, and we are struggling to find it.

Growing up in the San Francisco Bay Area, my experiences in public schools were filled with students from all ethnicities who were encouraged to learn and embrace languages and cultures beyond American English.

Marion Hmelar sits at Baker Beach looking out toward Golden Gate, the strait that almost all Chinese immigrants entered the United States through, including her father.

Marion Hmelar sits at Baker Beach looking out toward Golden Gate, the strait that almost all Chinese immigrants entered the United States through, including her father.

For my mother, who went to the same school district I attended, four decades prior, that was not the case. “There were very few Asian families, at least at my school,” Marion Hmelar said. “There were only two other Chinese kids besides myself.”

Dr. Chao Fen Sun, a professor of East Asian Language and Culture and Linguistics at Stanford University, is a native Cantonese speaker and teaches Chinese grammar. He has lived in the San Francisco Bay Area for over 30 years.

His kids grew up in the Bay Area, navigating the intersectionality of American life while maintaining their cultural identity.

“They say America is a melting pot,” Sun said. What they mean is that you become a part of this country but lose yourself entirely.

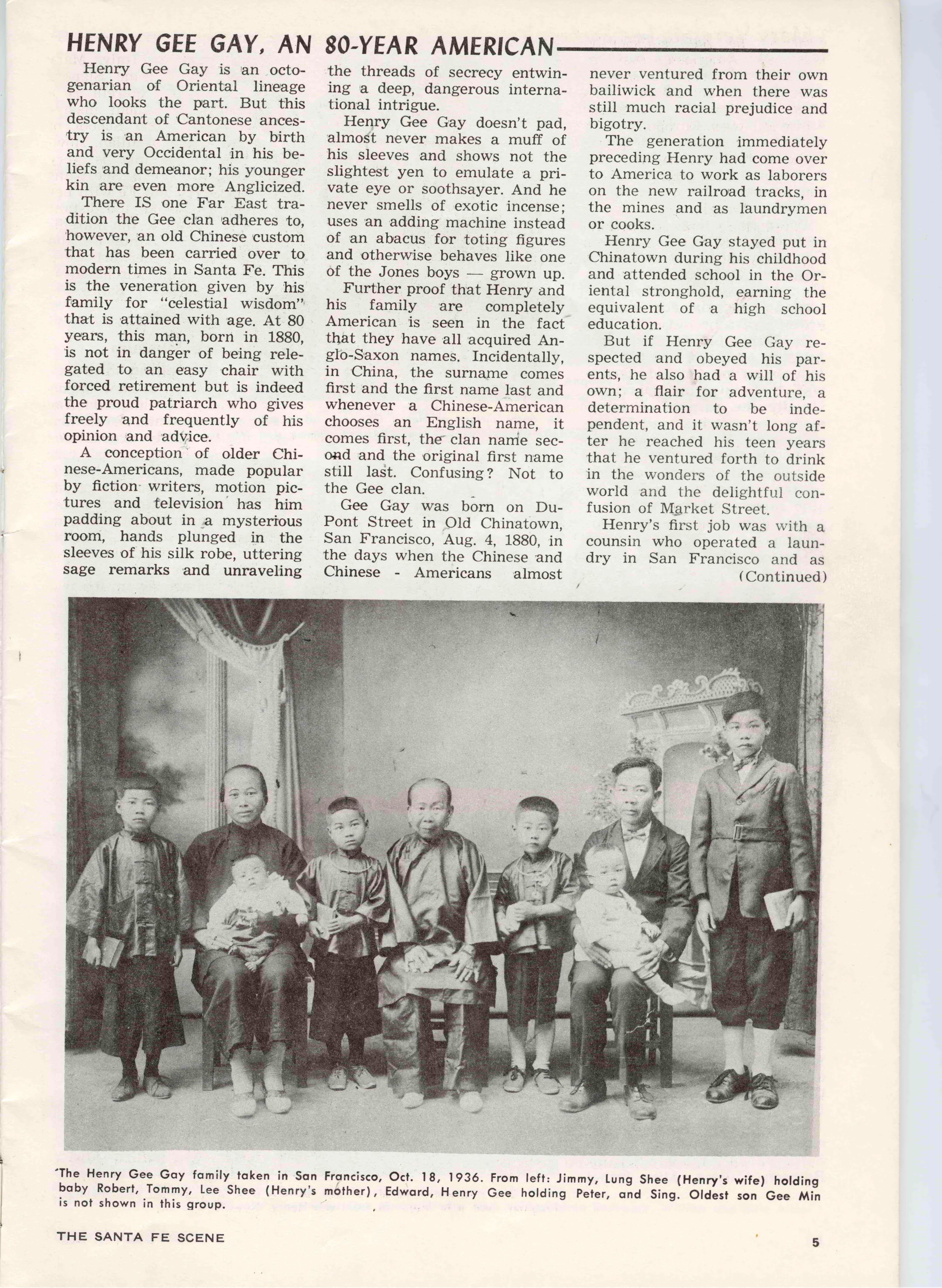

An article about the Gee Family’s assimilation in the Santa Fe Scene, Oct 29, 1960.

An article about the Gee Family’s assimilation in the Santa Fe Scene, Oct 29, 1960.

For Hmelar, this has been her lived experience since she was a child. “I’ve lost a lot of my memories of the Chinese language,” Hmelar said. Her grandmother was the only person she would speak Chinese to at home.

“I felt very self-conscious whenever anyone else was around. Sometimes, if I’d say something to my grandmother in Chinese in front of my friends, they would look at me like I was from a different planet. So I was very careful as to when and where I spoke to her.”

Reflecting on her knowledge of the language now, she points out that she is often hesitant about how to say things. “It used to come just spontaneously and now I need to think about the words that I’m trying to say before I can spit it out,” Hmelar said. This is a sentiment reflected in many second or third-generation Chinese Americans.

Watching the recent TV adaption of the novel Pachinko, by Min Jin Lee, a novel about the experiences of a multi-generational Zainichi family in Japan, a scene felt close to home. In a conversation with one of the main protagonists, a second-generation Zainichi in Osaka, he discusses his knowledge of Korean with an elder.

“He didn’t want them to learn that tongue. And now my own kids don’t even know the language in which their mother dreams,” the grandmother said.

Despite completely different circumstances and unique situations, the sentiment reflected by the grandmother referring to her children's lack of knowledge of Korean feels comforting in the unfortunate trend of having to abandon your heritage for the sake of survival through assimilation in a new place.

San Francisco and its surrounding communities are filled with immigrants. In the city alone, one in three residents is born outside of the United States.

With over 109 languages spoken in San Francisco and 124 in the surrounding Bay Area, government services need to be offered in languages other than English. According to the latest Language Access report from the City, 42.7% of residents over the age of five speak a language other than English at home.

While most Chinese speakers in the world speak Mandarin, most in San Francisco speak Cantonese. According to the San Francisco Unified School District, over 75% of all Chinese speakers in the district use Cantonese at home.

Cantonese, or variants of the Yue branch of Chinese such as that from Toisan, are dominant in the southern coastal region of Guangdong and other Asian countries. Since the 1840s, Chinese immigrants from the Cantonese-speaking parts of China have been immigrating to San Francisco and the United States.

While Mandarin speakers are on the rise, Cantonese remains the dominant language in San Francisco.

As concerns rise about younger generations understanding Cantonese and other Southern Chinese languages, efforts nationwide in the United States are at work to preserve it through schools, community groups and general education about the importance of these living languages.